Know Better, Do Better: The Complex Task of Talking About Race

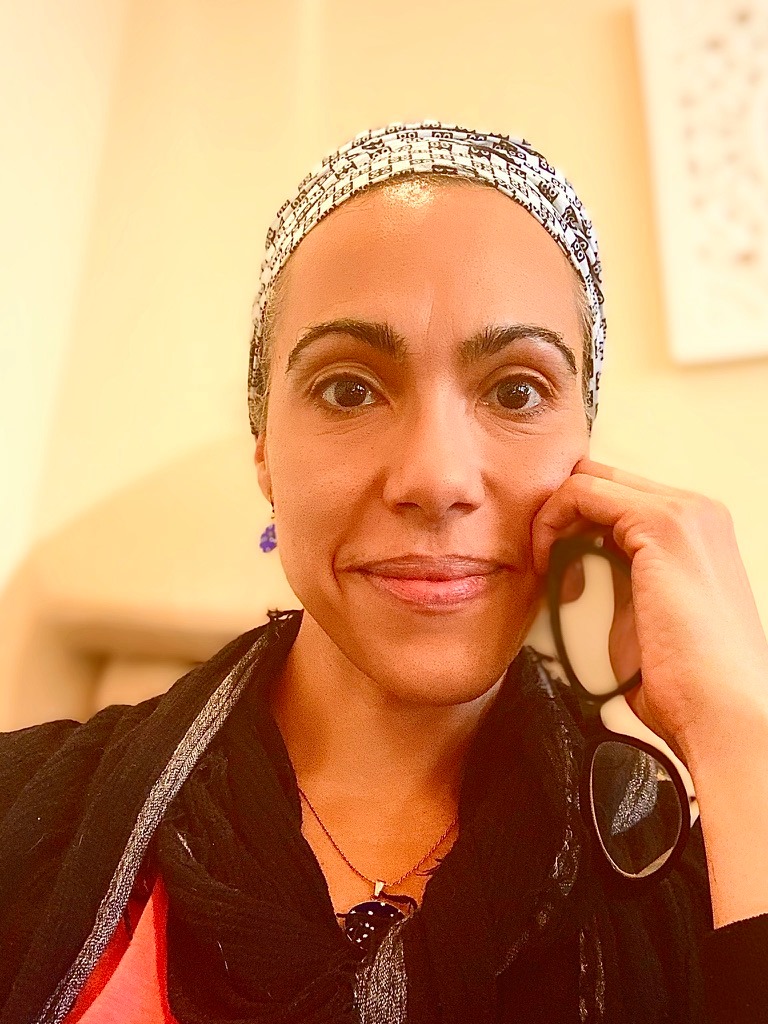

By Juko Holiday, PhD

I already know how the Facebook conversation is going to go, and a wave of frustration and deep sadness arises as I see it unfold in predictable fashion. The exchange, between people in a local neighborhood group, makes it clear that talking about racism is extremely difficult, especially on social media. It is particularly hard for white-identified people who do not feel or notice the impact of their race in their day-to-day lives to talk about the topic without first developing some skills and tools to do so mindfully.

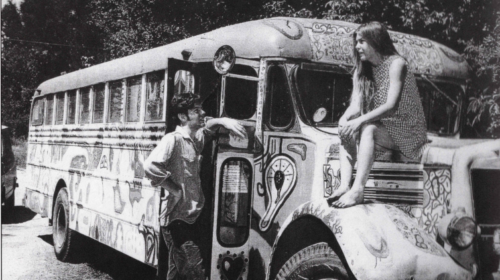

The arguments and reactions I read in the thread are not new to me, a black woman born in the wake of monumental civil rights legislation in the mid-to-late 1960s. My lifetime is a testament to the truth that laws written in books do not automatically translate to meaningful shifts of heart and mind. From being called an unprintable racial epithet by my school bus driver as a small child to being mistaken for live-in domestic help when being introduced to a professional colleague as an adult, I know we cannot legislate racism and bias out of existence. So, why is it so hard to talk about race? What do white-identified people who want to be part of the solution need to be aware of to move the healing process forward?

There are many answers to that question, but I would like to offer three ideas as possible starting points. First, it is critical to recognize that racism is systemic; it is not simply some bad white people being mean to some people of color. It is a system we inherited and each of us is socialized into it, without exception. The process of being immersed in it results in bias that is often unconscious, and becoming aware of how pervasive it is means recognizing that it has established a norm of white superiority and black and brown inferiority. This is heartbreaking and heavy, but when confronted can be untangled.

Second, it is critical to come to conversations about race with awareness of one’s own knowledge and understanding gaps, and being willing to practice humility as opposed to defensiveness when those gaps are pointed out. Witness, for example, the reaction some people have upon encountering the phrase “Black Lives Matter.” A common response is “All Lives Matter,” which reflects a gap in understanding the historical context that gave birth to the slogan. “Save the Whales” is not an insult to other sea life; “Protect the Redwoods” does not inspire informed people to say “All Trees Are Important.” With an empathy and/or knowledge gap around the particular threats to whales, Redwoods, and black lives, it is difficult to engage in meaningful conversation about those topics, even if one disagrees with the idea that any one of those particular forms of life is worthy of focused attention, protection, and care.

Lastly, conversations about race are hard because they bring up tough emotions. Fear and avoidance of those uncomfortable feelings trigger our sympathetic nervous system, which activates our “fight, flight, freeze, or feign” response. This response cuts off full access to our prefrontal cortex, which is the part of the brain that allows us to access our robust human capacity for reason, understanding, and empathy – all critical to doing the work of racial healing. From rage to shame to guilt to active malice to overwhelm, learning to observe strong feelings without allowing them to hijack your nervous system is a skill that can help you stay grounded in any difficult conversation, not only those about race.

As George Floyd was being murdered, he cried out for his deceased mother. In the Buddhist faith, there is this teaching, meant to help us access deep empathy for others, that all living beings have at one time been our own precious child and we, their devoted parent. Moving past the predictable stumbling blocks that prevent transformative conversations about race is a way to respond to his cry with radical compassion. We can untangle this suffering and find wholeness; we can learn to know better so we can begin to do better by each other.

Dr. Juko Holiday is a Ben Lomond business-owner who specializes in using integrative tools to support people living with grief and trauma. Read more about her work at jukoholiday.com