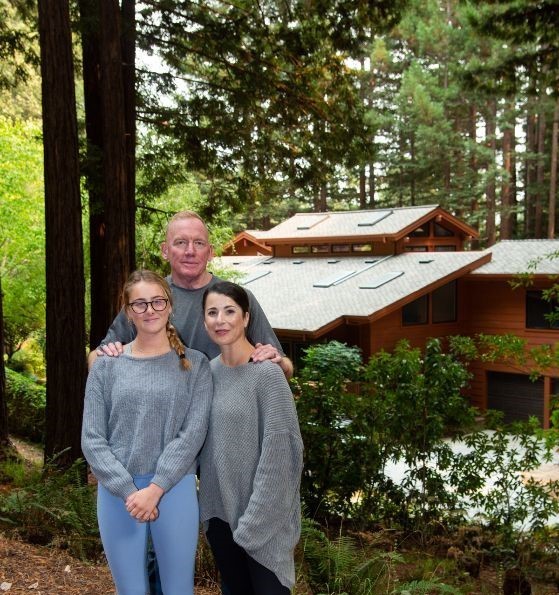

From Denial to Grief and Gratitude

A firsthand perspective on surviving a fire that “couldn’t happen”

By Jayme Ackemann

Every fire evacuation isn’t as dramatic as those middle-of-the-night knocks our neighbors in Boulder Creek got, but mine was every bit as terrifying. The CZU Lightning Complex fire evacuation order came down for Ben Lomond, the San Lorenzo Valley town where I live, on August 18. It was one of those days when the weather felt exceptionally hot and still. Until then I had been treating the smoke that hung over the region like a nuisance, never expecting fire would finally come to our asbestos forest.

Local fire volunteers and Cal Firefighters had long thought of the Santa Cruz Mountain coastal redwood forest as protected from the kinds of massive blazes we see today thanks to its cool, damp climate, and the natural fire resistance of these towering trees we live under. But climate change has heightened the stress on these trees through decades of increasingly frequent droughts.

Out of the Fire

On the day the evacuation order came down for Ben Lomond my brain was still struggling to process the reality of the fire chewing its way through the state park system that borders our neighborhood. Suddenly, the canyons and creeks we could hike to directly out our front door were burning.

There are all sorts of lists to help fire evacuees figure out what to take. Maybe next time, we’ll use those. Instead, we dashed through the house taking down treasured art, grabbing important records and jewelry and enough clothing to get through the night. You think you know what’s important until you are driving away from your home as a fire rages towards it. You realize that your heart lives in the wooden beams over the living room, the favorite spot on the couch, the kitchen where you’ve made a million meals, and you are leaving it behind.

On our first night of evacuation, we made it as far as a friend’s home in Scotts Valley. It was just a 10-minute drive, but it seemed so improbably far away. A fire that could threaten both Boulder Creek and Scotts Valley would be a monster. There was no way it could get there – our redwoods would slow it down. This is what my husband and I told each other as we watched the ash fall on their front porch. The next day Scotts Valley would also be ordered to evacuate, which is how we found ourselves pulling into my dad’s El Dorado Hills driveway loaded down with our things, covered in ash and smelling of smoke. There was relief in being “out of the fire” and that is when the tears began to fall.

Red, Sore Eyes

We cried because, already, the stories of friends who had lost homes had begun to roll in.

We cried because there was so much we didn’t or couldn’t take. At the last minute, with our cars already packed, our oldest daughter asked us to save her grandma’s metal sun and her crystal collection. We moved them into a clearing under a grate and hoped they would survive the fire.

For 13 days, the tears rarely stopped. We cried because every day in press briefings Cal Fire representatives were telling us they didn’t have the staff, equipment or resources to adequately fight the huge number of fires that had erupted across the state. We cried because the smoke just hung in the air, making it impossible to bring in air support. We cried because my firefighter brother-in-law, who was fighting on the fire’s front lines, called each night with bleak news.

The fire burned more than 20 percent of Santa Cruz County and nearly 1,500 structures, among them the homes of a girlfriend in my book club, my daughter’s Spanish teacher, and a former coworker.

We talk to each other in the language of survivors, about our gratitude for the emergency responders, and our grief for our community and our friends. We talk about the guilt that comes with having a home to return to when so many others have lost so much.

Buried Pathways

When the pandemic settled over the United States in March, my family started hiking. We weren’t alone. In those early days, parks and beaches were being overwhelmed by visitors looking for a way to get out of their house. We hiked up to the Truck Trail in Fall Creek behind our house and made it all the way to the park boundary.

Much of that is now burned, which is not all bad news.

Redwood forests are meant to burn. The trees actually benefit from a certain amount of fire. The forest floor will be cleaner and healthier, reducing the likelihood of devastating future fires. Good news out of Big Basin confirms this as the old-growth trees considered to be the “Mother” and “Father” of the forest still stand.

Even before this fire, the responsibility for managing the forest and our properties was becoming more challenging via new county building codes and regulations meant to keep the home safer in the event of a fire.

Some older homes couldn’t be defended because the properties were overgrown and the growth on those properties could have created the “slop over” effect that set a neighbor’s yard on fire.

But what about the state park next to us? The Fall Creek drainages could smolder for weeks; the fire was deep in some of those canyons and difficult to reach. Is the state parks system doing its part to reduce the possibility of these mega-fires taking off in densely forested canyons only to spill out into our neighborhoods?

In early August, my husband and I had hiked from the bottom of the canyon up to our house, climbing over long-fallen trees, making our way along narrow paths through dense foliage. Ironically, we commented to each other about all the tinder and about what could happen in a fire in the park.

Coming Home

Your imagination is your worst enemy when a wildfire forces you to evacuate. Wildfires don’t carry tracking chips; you can’t look it up on “Find My Friends” to see how close it’s getting. That’s part of the trauma – the lack of information.

But as we made the return trip to our mountain hamlet in September, the valley seemed largely untouched from Felton to Ben Lomond. On the mountainside above town, sections of dead and burned trees cut a swath across the landscape and smoke still billowed from drainages burning deep in the hills. Rows and rows of fire engines were parked on roadsides everywhere. We found a CHP officer parked in our driveway because we were the last house on our road allowed to return.

On the day we were told the fires were likely to reach our property within 24 hours, we were told there might not be enough resources to protect our road. We were told if the weather didn’t change to allow Cal Fire to send in air support, we would probably lose our homes. Instead all of those things went right, not just for us but for our extended family for whom the fires got as close as char marks on a garage and burned trees on their property. We were so lucky. And there’s guilt with that.

Our home stood largely untouched. Ash covered everything, and large burned-out chunks of tinder had fallen into our yard. The only evidence that fire got close to our house were some small burns that had started in the ivy below—ivy that is going to come out this year.

These things all seemed strange but also strangely comforting. Here were the heroes who had come to protect us when we could not stay to protect ourselves. We were so grateful.

Invisible Burns

In January 2020 massive bushfires broke out across Australia. It sounded as though the entire continent was burning down as we watched from afar. During those fires, the daughter of an Australian dairy farmer, Georgia Wilson, penned this poem. I leave you with her words:

“It is complete devastation. It is utter heartbreak. It is an emotional roller coaster.

It is having no sleep. It is not knowing what to do next. It is red, sore eyes.

It is having no power or communication. It is the separation of families.

It is grief. Anger. Guilt.”

It is all of these things.

Fire burns the psyche too. As San Lorenzo Valley repopulated there was a marked increase in the number of smoke and fire calls coming into the local dispatch. If everything smells like smoke, it’s hard not to wonder if something is on fire. Smoke is no longer a nuisance for me. It’s a warning. One we should all heed.

Jayme Ackemann lives in Ben Lomond with her husband Dean, where they raised their daughters Cassie and Zoe. After 15 years of commuting, Jayme founded Contact Public Affairs to focus on local outreach, communications, and government relations. Jayme is also a local writer who focuses on transportation, infrastruction, environmental issues, and local politics.

The article was originally published in longer format in Climate Magazine.

Photos left to right: Jayme Ackemann hikes through fire damage near her home, smoke continues to billow from a stump fire near the Ackemann home, Jayme Ackemann and her daughter Cassie on a spring 2020 hike through Big Basin before the fire

Feature photo: Ackemann family poses for a portrait in front of their Ben Lomond home. From left to right: Zoe, Dean, Jayme

Photos contributed by Jayme Ackemann

Follow Jayme on Twitter at https://twitter.com/JaymeAckemann