SLV Homeowners Could Bear the Cost of State’s Proposed Rules for High Fire Risk Neighborhoods

By Jayme Ackemann

According to the state’s proposed rules changes for high fire risk neighborhoods, some San Lorenzo Valley communities are “missing infrastructure.” This is a sophisticated way of saying the roads create hazards for emergency vehicles accessing our neighborhoods.

If the Board of Forestry and Fire Protection passes their proposal it would require roads in high fire risk communities to be improved to a minimum of between 12 and 14 feet wide and a grade no steeper than 16%. For private road owners and associations, the cost of upgrading this “missing” infrastructure may be overwhelming and prohibitive.

Slow CZU Fire Recovery

A community-centered approach would seek to put families back on their properties as efficiently as possible. The county’s process – by most accounts – is not that. The latest proposal could create further obstacles for those families.

The majority of privately owned roads in Santa Cruz County are in San Lorenzo Valley. For local homeowners, absorbing the burden of an unfunded mandate that could affect their homeowner’s insurance or resale value is daunting.

The San Lorenzo Valley also has some of the lowest per capita income levels in the county, making the burden on these unincorporated communities even heavier to bear without assistance from the county or state.

In 2017 following a mudslide that temporarily blocked one privately maintained road in Scotts Valley, County Supervisor Bruce McPherson told the Press Banner his office’s request for federal emergency funding was rejected. If the new rules are adopted, those demands are going to get louder and District Five will be the area hardest hit by the changes.

It’s time to consider a San Lorenzo Valley council to help amplify San Lorenzo Valley voices.

A similar example would be the Midcoast Community Council established by San Mateo County’s geographically isolated, unincorporated coastal communities. SLV needs a more effective and visible way of communicating its views. Incorporated communities rely on city staffers to coordinate with the county and elected council members to raise concerns when their community is overlooked.

In other words, the “squeaky wheel gets the oil.”

It may be time to get organized.

“Missing Infrastructure”

“The result is for these older developments, there is no local entity or government entity to help manage missing infrastructure,” Santa Cruz County Fire Safe Council Executive Board Member Marco Mack remarked in a recent Santa Cruz Sentinel story.

Mack’s observation has a lot to do with the challenges of merely implementing the kind of onerous regulations under discussion in unincorporated areas with privately-owned roads – like us.

If we are going to discuss “missing” infrastructure and the lack of local entities or government to help manage it, there are a few numbers we need to consider.

143,960 – The number of Santa Cruz County residents who live in unincorporated parts of the county.

More than 50% of the 273,123 people who live in Santa Cruz County currently have only one local elected representative to whom they can turn for support. Their County Supervisor.

4 – The number of incorporated cities within the county borders. They include Watsonville, Capitola, Santa Cruz, and Scotts Valley.

Take note of the fact that many of our county’s lowest-income residents live in unincorporated areas where their access to government services and participation may be further limited by geographic isolation and a lack of reliable public transportation.

0 – The amount of local control we have over sweeping decisions that could change the way we live.

The Midcoast Community Council was born out of a need for San Mateo County’s isolated, rural communities to give feedback to the County Supervisors making decisions in faraway Redwood City. Poor roads and infrequent public transportation made it difficult for the area’s residents to communicate their concerns to the Supervisors who hold their meetings on the other side of the county.

MCC is funded through a $3,000 stipend from the county to cover meeting expenses, communications, and outreach. The members are elected from the local community but serve without staff. Their votes on a range of issues from parks to public works help to inform their District Supervisor in the same way a city council may voice their concerns regarding an issue before the county’s board.

The concept of a municipal advisory council is not entirely new to the San Lorenzo Valley. In 2007, the Felton Business Association raised the possibility in light of development projects initiated at the county level with little input from stakeholder community members. The FBA’s stated mission for a notional Felton Municipal Advisory Council was to “provide a community forum for the public to hear about and comment on a variety of local and countywide topics. Members are tasked with gathering input, making recommendations based on that information, and relaying it to the appropriate decision-making body, such as the board of supervisors.”

If we learn anything from 2020, it should be the importance of community. San Lorenzo Valley has always pooled its resources and come together to support one another. When we can’t do it on our own, the county is supposed to be there to help navigate those challenges.

We’ve always been #SLVStrong, maybe it’s time to get #SLVLoud?

Jayme Ackemann is a public affairs consultant and freelance writer. Ackemann has worked on major capital investments and water infrastructure capital construction projects in the Bay Area. Jayme has been a resident of Ben Lomond for more than 15 years.

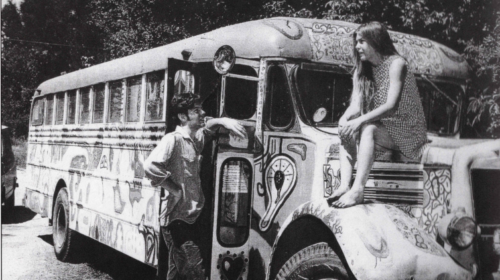

Photos by Thomas Andersen

Hope folks will sign the petition: https://sign.moveon.org/petitions/san-lorenzo-valley-community-council?source=facebook-share-button&time=1626726712&utm_source=facebook&share=b7800f40-9f64-4447-a2d1-7849be9b2096&fbclid=IwAR29I9-XSnZrH8stpheNVFQRChTt7JcKDwy2tj_j0uT_9ZfH2PCdXG-9Blc