Flumes: Lifelines of the 19th-Century Redwood Rush

By Mary Andersen

In the Santa Cruz Mountains during the 1800s, the air frequently hummed with the thunder of falling redwoods and the distant roar of rushing water. Felton, then a nascent lumber boomtown on the San Lorenzo River, stood at the heart of this industrial activity. Here, flumes – ingenious wooden waterways engineered to defy gravity – transformed the region’s forest wilderness into a conduit for America’s insatiable hunger for timber.

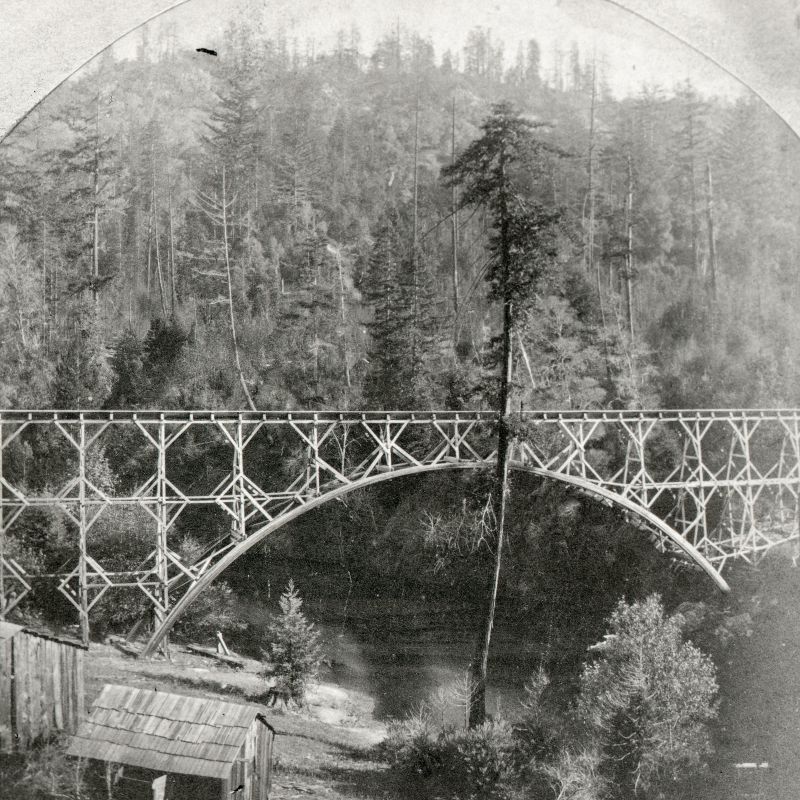

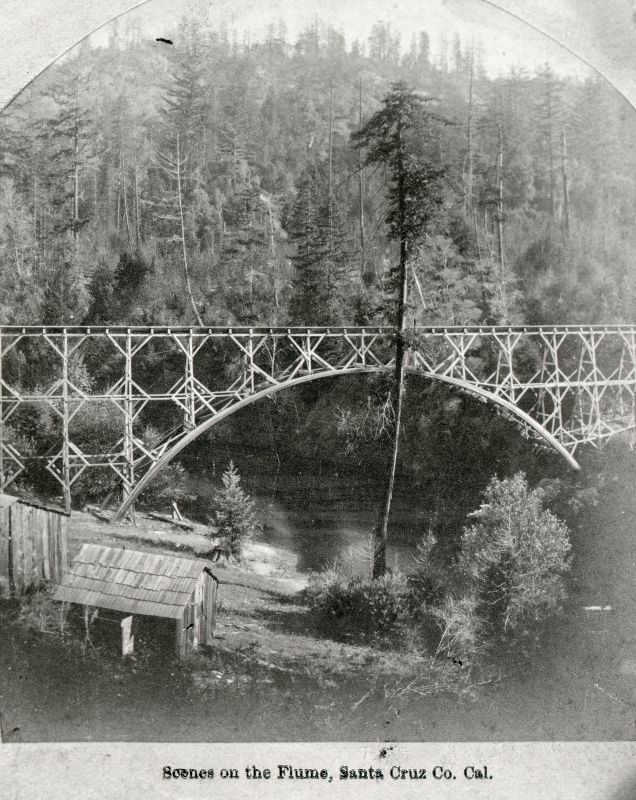

These V-shaped troughs, often 40 inches wide and perched on spindly trestles, were vital arteries of the lumber trade, ferrying boards, beams, and split products from remote mills to coastal markets.

Flumes emerged as a 19th-century innovation born of necessity. The Gold Rush of 1849 had scorched California’s timberlands, driving prices skyward and luring entrepreneurs to the state’s lush redwood groves. Yet, the Santa Cruz Mountains’ steep grades and serpentine rivers defied traditional transport. Ox teams bogged down in mud; early railroads faltered on unyielding terrain. Enter the flume: a water-filled chute crafted from the very lumber it carried.

Workers, enduring grueling labor, felled colossal coast redwoods using crosscut saws and wedges. These giants were milled into boards along tributaries, then loaded into the flume’s current for a swift, 10-mile descent. Gravity and diverted streamflow propelled the cargo, dodging chutes and drops that tested the structure’s integrity.

In Felton, the San Lorenzo Valley Flume & Transportation Company reigned supreme. Incorporated in August 1874 by Frederick A. Hihn and Edmund J. Cox, the company spanned from the river’s headwaters near Boulder Creek to Felton’s bustling depot. Construction began in 1875, a Herculean feat: crews hammered together 60,000 board feet of redwood planking daily, bridging ravines with 100-foot trestles and snaking the line through fern-choked gulches.

By October 1875, the flume sprang to life, its inaugural run was determined to be a success. Felton’s strategic perch – seven miles from Santa Cruz – made it the perfect terminus. Here, the flume disgorged its haul onto sorting yards, where workers sorted pine, fir, and prized redwood for kiln-drying and planing.

The flume’s role in Felton’s lumber economy was profound. It sustained a constellation of mills: the company’s massive operation near Garrahan Park, the Peery Mill in Lorenzo and Pacific Mills in Ben Lomond. These fed a valley-wide network, producing shingles, barrel staves, and framing for San Francisco’s postwar rebuilds. At peak, the flume churned out 10 million board feet annually, employing hundreds in logging camps, millwright shops, and flume-tending crews who patrolled for leaks and logjams. “Flume herders,” armed with pickaroons and sheer grit, balanced on narrow walkways to pry free tangled boards.

Yet, prosperity was fleeting. The 40-inch flume strained under demand, leaking prodigiously and parching in summer droughts when mountain streams dwindled. The railroad was built from Alameda to Santa Cruz in 1880. It would not replace the flume from Felton to Boulder Creek for another 5 years. It would however allow lumber to be shipped directly from Felton to San Jose and beyond by train. Reality bit harder: overharvesting thinned the forests, and the Santa Cruz & Felton Railroad’s completion in 1875 undercut the flume’s monopoly. By 1888, then owned by South Pacific Coast Railroad, the wooden behemoth fell silent, dismantled for scrap amid bankruptcy rumors. Its legacy lingered, however – Felton’s rail yards boomed, shipping redwood to fuel California’s Gilded Age.

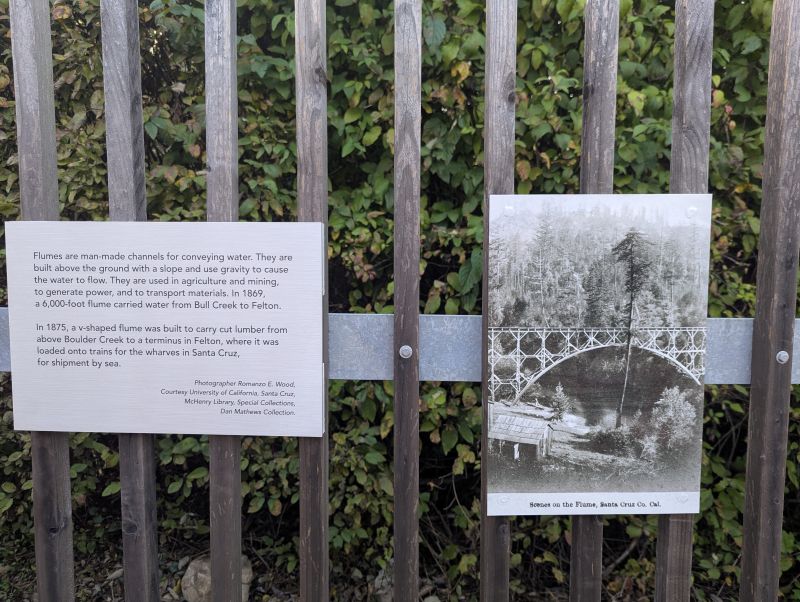

At the Felton Library, two new signs adorn the patio fence. They were designed and funded by Felton Library Friends to help explain the small flume replica’s reference to Felton’s history. Lisa Robinson of the SLV Museum obtained the photo of a local flume circa 1875 (by Romanzo.E. Wood, courtesy UCSC Special Collections, Dan Mathews collection). She also wrote the text for the sign about the uses of flumes that reads, “Flumes are man-made channels for conveying water. They are built above the ground with a slope and use gravity to cause the water to flow. They are used in agriculture and mining, to generate power, and to transport materials. In 1875, a v-shaped flume was built to carry cut lumber from above Boulder Creek to a terminus in Felton, where it was loaded onto trains for the wharves in Santa Cruz, for shipment by sea.”

Special thank you to Lisa Robinson at the San Lorenzo Valley Museum for providing feedback on the article.

Featured photo: UCSC Special Collections, Dan Mathews collection

Mary Andersen is a journalist and Publisher of the San Lorenzo Valley Post, an independent publication dedicated to the people, politics, environment, and cultures of the Santa Cruz Mountains. Contact mary@slvpost.com